Aim

While investigating the existing literature for the mechanisms behind algal small heat shock proteins, we realised that species studied for conservation are very underserved by protein structure research. All that could be summarised was that small heat shock proteins form dimers which may then assemble further into 12mer-32mer complexes. (1) This served as our first lead in investigating the holdase function of HSP22E/F.

A protein’s structure determines its function. A peptide sequence is composed of amino acids that have side chains with various chemical properties. Due to the particular sequence of these amino acids, various side chains at different distances will attract and repel, and then self-assemble into its native state(s) in a matter of milliseconds. (2) This is important to remember when performing molecular dynamics simulations. Such simulations are usually on the timescale of nanoseconds (e-9) while protein folding happens on the order of milliseconds (e-3) and protein-protein interactions like that of dimer formation may take seconds as evidenced in typical molecular assays. Longer simulations require ever more computational resources and time to simulate. As such, molecular dynamics are best for refining protein structures that are suspected to be quite close to their native conformation.

Structure Determination

There are no known heat shock protein structures from C. reinhardtii that have been experimentally determined. However, the amino acid sequences of C. reinhardtii heat shock proteins are known, specifically - HSP22E, HSP22F and HSP22G - which our team decided to predict the structure of to help with the understanding of their function. These heat shock proteins were chosen as HSP22G was predicted to localise to mitochondria and while HSP22E and HSP22F localised to chloroplasts. (1) After running a blastp (3) search on all of these proteins with the PDB database, (4) it was found that HSP22G had quite low sequence identity of ~25%, insignificant E values and low query coverage with the other known structural PDB hits. In contrast, HSP22E and HSP22F both had higher percentage identities ranging from ~28-50%, significant E values and higher percentage coverage. For this reason, the team changed to predict the structures of HSP22E and HSP22F instead of HSP22G. Even though the hits for HSP22E and HSP22F were better than the hits for HSP22G, they were all very similar and it was hard to definitively select one to be used as a template for homology modelling. A fold recognition and template modelling server, I-TASSER (5–7), was used to create models for HSP22E and HSP22F based on the best templates found by I-TASSER using a threading approach. The highest ranking models for both the HSP22E and HSP22F sequences were chosen as the starting structural models to be further refined and used in future molecular dynamic simulations (Figures 1 and 2). Both the I-TASSER models were based on the same PDB template structure 1GME (8) which is another eukaryotic small heat shock protein that forms a 12-mer complex made up of 6 dimers bound together. Interestingly, the literature on C. reinhardtii small heat shock proteins propose that they form dimers and further form larger oligomers ranging from 12 to 32 subunits (1).

Structure Refinement

I-TASSER unlike other template based methods builds models with multiple templates rather than a single template sometimes resulting in models with backbone torsion angles that are energetically unfavourable. More broadly the practice of imposing the structure of a known protein onto our similar protein aims to get a largely correct global topology but might not be so accurate at a local level. (9) As such, refinement must be conducted to ‘flex’ structures into more energetically favourable configurations. MolProbity, (10) was used to evaluate the viability of structures before and after each stage of refinement. Refinement was first targeted at improving the rotamers for the local structure and then globally improving atom clashes.

We hope that our exercise in refinement will shed some light on rather opaque metrics and software. Measures to pay particular attention to:

- Clashscore

- Number of serious overlap between pairs of nonbonded atoms

- Lower is better

- Poor/Favoured Rotamers

- Quality of placement of side chains

- Lower is better

- MolProbity Score

- Log-weighted combination of clashscore, percentage Ramachandran not favored and percentage bad side-chain rotamers

- Lower is better

Pre-refinement MolProbity

Model refinement with GalaxyRefine

First, the monomers were refined with GalaxyRefine, which is suited to improving template based structures as it remodels side chains (similar proteins generally differ in the side chains but have similar backbones) to improve the local structure accuracy. (11) Of the five generated models, MODEL 1 was chosen for both HSP22E and HSP22F to proceed with further refinement as all models similarly improved the side chain rotamers.

Overall, the post GalaxyRefine MolProbity summary statistics had large improvements in poor rotamers (35 -> 2) and moderate improvements in every other measurement for both monomers.

Post-GalaxyRefine MolProbity

Model refinement with Gromacs

Gromacs is a molecular dynamics software that will essentially place your molecule in a box full of water molecules and let the molecule flex, tending towards a conformation of the molecule that minimises its energy. (12) The procedure that was used to refine all molecules going forwards was adapted from mdtutorials.com, particularly the “Lysozyme in Water” for the generated workflow and then “Protein-Ligand Complex” for the visualisation advice. (13) The forcefield chosen for these simulations was charmm27, (14) this was determined by looking at the forcefield most commonly used by MD papers on other small heat shock proteins. (15–17) This is a zip file of our scripts and mdp files, these are modifications of scripts and mdp files from our expert consultant Brian Ee.

Pre-refinement MolProbity

MD for HSP22E and HSP22F were run for 10 nanoseconds each and the last frame of the trajectories were converted into pdb files for further analysis. Looking at the post MD MolProbity statistics, the clashscores had vastly improved. This made sense as gromacs discouraged nonbonded atoms from being too close to each other. Although the number of poor rotamers increased, it only increased slightly. For both monomers the MolProbity score improved vastly compared to pre-refinement.

Dimer Docking

ClusPro Dimer Modelling

Previously stated, literature has hypothesised that small heat shock proteins form dimers and not much else is known about this dimer configuration. HSP22E and HSP22F only differ by 11 amino acids, and through phylogenetic analysis it is likely that the two very similar genes are the result of a recent gene duplication event. (1) An uncertainty that arose from this little information was whether these monomers form homodimers with themselves or whether there is something adaptive about the gene duplication and subsequent divergence of these two sequences. That is whether a HSP22E and HSP22F would form a functional heterodimer with each other. Another uncertainty is whether these small heat shock proteins are active and bind to denatured proteins as a dimer unit like IbpA-IbpB dimers (15) or as a larger oligomer complex similar to GroEL/ES complex. (18) The template structure 1GME used by I-TASSER is active as a dimer and uses its 12-mer configuration as a storage unit when the cell is not undergoing a heat response. (19)

Whether HSP22E and HSP22F are active as a dimer or oligomer, a dimer model was needed in order to act as the 6 subunits for the 12-mer model. The protein-protein docking server ClusPro (20–22) was used to generate structural models for a HSP22E/F dimer. The top two ranking models were superimposed over the 1GME dimer model to determine whether they aligned well and therefore were valid dimer models. However, both dimer models aligned strangely where one subunit would align almost perfectly while the other was close but at a different orientation to its 1GME part (Figure 11). Therefore the ClusPro dimer models did not resemble 1GME and were unlikely to be compatible with the 12-mer configuration. ClusPro performs rigid body docking where it does not allow for any flexibility or movement of different loops to be computationally feasible. However, proteins are not static but generally have flexible loops that could move out of the way for dimer formation, this could not be simulated in ClusPro. This is why the dimer models had slightly off orientations compared to 1GME and if some of the loops and turns of the models were slightly moved they would appear to align well. As such we decided to manually dock our dimers based on the 1GME template at the advice of our expert Brian Ee.

PyMOL Dimer Modelling

The monomers HSP22E and HSP22F were superimposed onto the 1GME dimer model in an attempt to generate a dimer model (Figure 12). HSP22E was aligned to chain A and HSP22F was aligned to chain B of the 1GME dimer, meaning that the orientation of the beta sheets was imposed onto our dimer model. We suspected this to be important to creating wall-like dimer blocks that form into large oligomers like 1GME. Unfortunately, the N-termini of the monomers overlapped when superimposed with one another. This is not physically possible since two atoms can not occupy the same x,y,z position. In order to create a model for a HSP22E/F dimer the clashing residues and secondary structures need to be remodelled.

De novo Loop remodelling

UCSF’s Modeller (23–26) program interface in Chimera was used to remodel HSP22E and HSP22F monomers to make the superimposition of monomers physically viable. Modeller refines existing segments by generating different possible conformations and it outputs five different models for the user to choose from. The team analysed the Modeller models and selected the best HSP22E and HSP22F models based on whether it appeared that loops had been repositioned to no longer cause clashes. Each model was then aligned to a different chain of 1GME to create a HSP22E/F dimer model (Figure 13). A few different variations of HSP22E and HSP22F models from Modeller were used to create trial dimers before the best combination of monomers was decided to be used for the final HSP22E/F model. Many of these dimer variations of monomers still experienced overlapping residues and so extra iterations of Modeller were carried out to further refine and remodel these clashing segments until they no longer clashed. Even though the best HSP22E/F dimer combination experienced no overlap there were still sections between HSP22E and HSP22F that almost came into contact with one another (Figure 14). At times some small alpha-helical structures which the team didn’t think were too structurally important were remodelled. However, it is a possibility that those removed alpha-helices were structurally important. Therefore dimer refinement was performed once again in order to solve this problem as well as to move the almost overlapping segments in the model further away from one another.

Dimer refinement

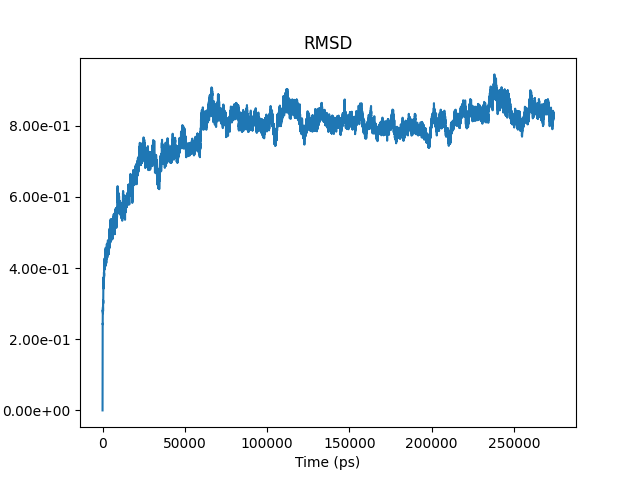

The dimer was simulated with the same procedure as the monomers but for a much longer duration. We ran this simulation for as long as we could (100+ hours of HPC time), with GPUs on UNSW’s computational cluster Katana. The reason for this longer compute time was to try to observe convergence of our dimer model. There is no hard definition for convergence but it generally means that the structure has settled into a conformation where energy is minimised. (27) To depict this, our expert Brian, drew this set of graphs to show how we could observe convergence. RMSD is the root mean square distance between pairs of equivalent alpha carbons between two structures. (28) Rg is the radius of gyration, this is a measure of the compactness of a structure. (27) In these mock graphs, convergence would be the common time at which the distance of both plots became quite consistent, signified by the dotted lines.

To really get an intuitive understanding of these graphs, they need to be examined in conjunction with the movement of the molecule. In this 275ns simulation you can see C-termini settling over time and the beta sheet core staying rather constant in both the graphs and the video. Given that the arms are settling in, we would expect convergence to be close.

We further investigated the extent of movement in the core of the protein. Both of these figures were created by only looking at the backbone atoms of the core of the dimer. The core was defined as all residues besides those in the flexible C-termini of the monomers in the dimer. Additionally, only backbone atoms were considered as side chains of residues (rotamers) can also have a lot of movement.

The RMSD was calculated by comparing the alpha carbons of the first frame of the 275nm simulation with every successive frame of the simulation (the trajectory). Over time it can be observed that the RMSD plateaus on the y-axis (distance in nanometres), within 0.1nm of a distance of 0.8nm, suggesting that the backbone of the core protein is reasonably stable. This is to say that from 50ns onwards the amount of difference between each successive structure conformation of the dimer, and the starting structure was quite consistent. In regards to the Rg of the backbone atoms of the core protein, convergence was not so convincing and would benefit with a longer simulation time. This would give us greater confidence as to whether the Rg fluctuating by 0.1 nm (2.18-2.28nm) is just fluctuations between many versions of energy minimised structures in which case it would have converged or if the range of Rg will shrink with further simulation time.

Future Directions

In Phase II, if the wet lab’s experiments find that the binding affinity between homodimers is higher than that of the E/F heterodimer, structural modelling of those homodimers and the large oligomer would be conducted. These structures would then be used in further simulations to investigate whether the HSP22 are active as dimers or large oligomers.

Additionally, the team was limited by time and therefore could not create a fully refined HSP22E/F 12-mer model (Figure 19). We simply aligned six of the HSP22E/F dimers onto a 12-mer assembly of 1GME to generate a physically impossible 12-mer configuration. There are obvious clashes between the six different dimers that model needs to be adjusted for. This would most likely require loop remodelling as well as the transposition of each dimer a bit further away from each other in order to let them fall naturally into place through a molecular dynamics simulation.

REFERENCES

- Rütgers M, Muranaka LS, Mühlhaus T, Sommer F, Thoms S, Schurig J, et al. Substrates of the chloroplast small heat shock proteins 22E/F point to thermolability as a regulative switch for heat acclimation in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Mol Biol. 2017 Dec 1;95(6):579–91.

- Kubelka J, Hofrichter J, Eaton WA. The protein folding ‘speed limit.’ Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2004 Feb 1;14(1):76–88.

- Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990 Oct 5;215(3):403–10.

- Berman HM, Westbrook J, Feng Z, Gilliland G, Bhat TN, Weissig H, et al. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000 Jan 1;28(1):235–42.

- Zhang Y. I-TASSER\: Fully automated protein structure prediction in CASP8. Proteins Struct Funct Bioinforma. 2009;77(S9):100–13.

- Roy A, Yang J, Zhang Y. COFACTOR: An accurate comparative algorithm for structure-based protein function annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012 May 8;40:W471-7.

- Yang J, Zhang Y. I-TASSER server: new development for protein structure and function predictions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015 Jul 1;43(W1):W174–81.

- RCSB PDB - 1GME: Crystal structure and assembly of an eukaryotic small heat shock protein [Internet]. [cited 2020 Oct 22]. Available from: https://www.rcsb.org/structure/1gme

- FAQ - I-TASSER [Internet]. [cited 2020 Oct 22]. Available from: https://zhanglab.ccmb.med.umich.edu/I-TASSER/FAQ.html#16

- Chen VB, Arendall WB, Headd JJ, Keedy DA, Immormino RM, Kapral GJ, et al. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010 Jan 1;66(1):12–21.

- Heo L, Park H, Seok C. GalaxyRefine: protein structure refinement driven by side-chain repacking. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013 Jul 1;41(W1):W384–8.

- GROMACS: A message-passing parallel molecular dynamics implementation. Comput Phys Commun. 1995 Sep 2;91(1–3):43–56.

- GROMACS Tutorials [Internet]. [cited 2020 Oct 27]. Available from: http://www.mdtutorials.com/gmx/index.html

- CHARMM: The Biomolecular Simulation Program [Internet]. [cited 2020 Oct 27]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2810661/

- Bhattacharjee S, Dasgupta R, Bagchi A. Structural Insights into IbpA–IbpB Interactions to Predict Their Roles in Heat Shock Response. In: Muppalaneni NB, Gunjan VK, editors. Computational Intelligence in Medical Informatics [Internet]. Singapore: Springer; 2015 [cited 2020 Sep 29]. p. 41–51. (SpringerBriefs in Applied Sciences and Technology). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-260-9_4

- Bhattacharjee S, Dasgupta R, Bagchi A. Structural Bioinformatic Approach to Understand the Molecular Mechanism of the Interactions of Small Heat Shock Proteins IbpA and IbpB with Lon Protease. In: Mandal JK, Satapathy SC, Kumar Sanyal M, Sarkar PP, Mukhopadhyay A, editors. Information Systems Design and Intelligent Applications. New Delhi: Springer India; 2015. p. 29–36. (Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing).

- Elucidation of the molecular mechanism of heat shock proteins and its correlation with the effects of double mutations S679A & K722Q in the catalytic dyad residues of Lon protease. Gene Rep. 2019 Sep 1;16:100438.

- Mayhew M, da Silva ACR, Martin J, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Hartl FU. Protein folding in the central cavity of the GroEL–GroES chaperonin complex. Nature. 1996 Feb;379(6564):420–6.

- van Montfort RLM, Basha E, Friedrich KL, Slingsby C, Vierling E. Crystal structure and assembly of a eukaryotic small heat shock protein. Nat Struct Biol. 2001 Dec;8(12):1025–30.

- Vajda S, Yueh C, Beglov D, Bohnuud T, Mottarella SE, Xia B, et al. New Additions to the ClusPro Server Motivated by CAPRI. Proteins. 2017 Mar;85(3):435–44.

- Kozakov D, Hall DR, Xia B, Porter KA, Padhorny D, Yueh C, et al. The ClusPro web server for protein-protein docking. Nat Protoc. 2017 Feb;12(2):255–78.

- Kozakov D, Beglov D, Bohnuud T, Mottarella SE, Xia B, Hall DR, et al. How Good is Automated Protein Docking? Proteins. 2013 Dec;81(12):2159–66.

- Webb B, Sali A. Comparative Protein Structure Modeling Using MODELLER. Curr Protoc Bioinforma. 2016;54(1):5.6.1-5.6.37.

- Martí-Renom MA, Stuart AC, Fiser A, Sánchez R, Melo F, Šali A. Comparative Protein Structure Modeling of Genes and Genomes. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2000 Jun 1;29(1):291–325.

- Šali A, Blundell TL. Comparative Protein Modelling by Satisfaction of Spatial Restraints. J Mol Biol. 1993 Dec 5;234(3):779–815.

- Fiser A, Do R, Sali A. Fiser, A., Do, R. K. & Sali, A. Modeling of loops in protein structures. Protein Sci. 9, 1753-1773. Protein Sci Publ Protein Soc. 2000 Oct 1;9:1753–73.

- Mackay DHJ, Cross AJ, Hagler AT. The Role of Energy Minimization in Simulation Strategies of Biomolecular Systems. In: Fasman GD, editor. Prediction of Protein Structure and the Principles of Protein Conformation [Internet]. Boston, MA: Springer US; 1989 [cited 2020 Oct 27]. p. 317–58. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4613-1571-1_7

- Lobanov MYu, Bogatyreva NS, Galzitskaya OV. Radius of gyration as an indicator of protein structure compactness. Mol Biol. 2008 Aug 1;42(4):623–8.

- Carugo O. Statistical validation of the root-mean-square-distance, a measure of protein structural proximity. Protein Eng Des Sel. 2007 Jan 1;20(1):33–7.