Engineering Cycle

iGEM Stockholm 2020 presents its engineering cycle (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Engineering cycle for our project

In order to build a scientifically rigorous project, iGEM Stockholm proceeded by following the engineering cycle and improving little by little each and every experiment performed during the summer. We started by finding a problem we wanted to solve and gathering information about it until a clear goal could be defined. Then we divided our project into subtasks and modules. We designed experiments that would help us build and prove the viability and success of our Microbial Fuel Cell (MFC) biosensor. We modelled our main goal, the oscillatory circuit that would help detect and identify different pollutants, in-silico. We built a MFC and assembled and tested our constructs in parallel. We characterized the MFC and the constructs, analysed the results and drew conclusions for each. For each problem encountered, we followed the cycle again to optimize our experiments and get better results.

Problem identification

In the first few months of iGEM, we gathered to find a project that was interesting and meaningful to the full team. In April-June, it became clear that we wanted a project related to the pollution of the Baltic sea, as this was a problem which we had all heard of and that directly affects the area where we live.

Gathering information

We dived into the problem of sea pollution by reading literature and contacting researchers that worked both in the field of microbiology and pollution. We looked for reports on pollution in the Baltic sea to see what pollutants were the most problematic and what their origin was. In particular, the Helsinki Commission published in the spring a series of reports Undeman, 2020; McLachlan & Undeman, 2020; Undeman & Johansson, 2020; Johansson & Undeman, 2020 highlighting the levels and effects of dioxins, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), flame retardants such as polybrominated diphenyl ethers and polybrominated biphenyls, diclofenac, perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS) and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs). We chose to focus on two types of pollutants PCBs and PFOS, for which we found promoter parts engineered and/or studied by previous iGEM teams (BBa_K2911000 and BBa_K1155001).

Once we chose to work on a microbial fuel cell for these pollutants' detection, we figured that two approaches could be taken: either increasing the electrical production of the cell or taking a novel approach to distinguish and quantify pollutants. Because previous approaches to increase electricity production had not been very successful, we decided to use synthetic biology to create unique electrical signals for different pollutants.

Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 is commonly used in microbial fuel cells for electricity production thanks to its MtrB gene. However, most iGEM teams create parts that work in E. coli and we wanted to contribute to the creation of new parts that could be used by as many teams as possible in the future. Besides, most microbiology techniques and protocols are easily adapted and troubleshooted in E. coli. Thus, we developed the idea of having a modular system: a system where most of the synthetic biology work of pollutant detection would be performed on E. coli, and where the electrical output would be given by Shewanella oneidensis MR-1. To connect these two modules, we chose to take advantage of quorum sensing molecules, molecules that can transmit signals between different cells.

Defining a goal

The final goal of our project was to engineer E. coli and S. oneidensis strains so that their growth in MFC, in the presence of pollutants could give an oscillating electrical output that would be unique for each pollutant.

Plan and define subtasks

Since our project is by essence modular, it was easy to divide the tasks: we had to work in parallel on:

- engineering E. coli so that it detects pollutants and emits quorum sensing (QS) molecules as a result;

- engineering a Shewanella oneidensis MtrB knockout strain (unable to produce electricity in normal conditions) so that the received QS signal from E. coli activates a conditional electrical pathway (production of electricity only if a pollutant is detected);

- designing a genetic circuit that gives a unique oscillating output when a certain pollutant is detected;

- building a functional microbial fuel cell in which the strains could perform their activities.

Figure 2 below shows a detailed division of the tasks.

Figure 2: Division of engineering tasks

Design

Circuit

We used the SnapGene software to design the following parts and circuits using the Biobrick format.

| Biobrick | Code | Construct | Aim |

|---|---|---|---|

| BBa_K3440000 | A | Pconst-RBS-LuxI-Myc-DT | Show that LuxI can be expressed under constitutive promoter |

| BBa_K3440002 | B | Pprma-RBS-mCherry-DT | Test leakiness of Pprma |

| BBa_K3440001 | C | PbphR1-RBS-mCherry-DT | Test bphR1 promoter leakiness and compare expression with/without PCB. |

| BBa_K3440003 | D | Plux-RBS-GFP | Test leakiness of Plux |

| BBa_K3440004 | E | Prhl-RBS-GFP | Test leakiness of Prhl |

| BBa_K3440005 | F | Pprma-RBS-LuxI-Myc | Show that LuxI can be expressed under prma promoter, and compare expression with/without PFOS.Final construct E. coli PFOS. |

| BBa_K3440006 | G | Pconst-RBS-RhlI-Myc | Show that RhlI can be expressed under constitutive promoter |

| BBa_K3440007 | H | Pconst-RBS-AiiA-Myc | Show that AiiA can be expressed under constitutive promoter |

| BBa_K3440008 | J | Pconst-RBS-RhlR-Myc-DT | Show that RhlR can be expressed under Pconst |

| BBa_K3440009 | L | Pconst-RBS-bphR2-Myc-DT | Show that bphR2 can be expressed under Pconst |

| BBa_K3440010 | M | Pbphr1-RBS-LuxI-Myc | Show that LuxI can be expressed under bphR1 promoter, and compare expression with/without PCB. |

| BBa_K3440011 | N | Pconst-RBS-GFP-DT | Show that the constitutive promoter works |

| BBa_K3440012 | O | Pconst-RBS-RHlR-Myc-DT-Prhl-RBS-GFP | Show that Prhl promoter can be activated in the presence of AHL and RhlR expression |

| BBa_K3440013 | P | Pconst-RBS-LuxR-Myc | Show that LuxR can be expressed under Pconst |

| BBa_K3440014 | Q | Pconst-RBS-LuxR-Myc-DT-Plux-RBS-GFP | Show that Plux promoter can be activated in the presence of AHL and LuxR expression |

| BBa_K3440015 | K | RhlI-RBS-Aiia | Intermediate part used for construction |

| BBa_K3440016 | I/Ch5 | Pconst-RBS-MtrB-Myc | Show that MtrB can be expressed under constitutive promoter |

| BBa_K3440017 | L3B | Pconst-RBS-bphR2-Myc-DT-Pbphr1-RBS-mCherry | Show that bphR1 promoter can be activated by expression of bphR2 (and better with PCB) |

| BBa_K3440018 | P32 | Pconst-RBS-bphR2-Myc-DT-Pbphr1-RBS-LuxI | Full construct for detection of PCB and expression of LuxI. Final construct PCB in E. coli |

| BBa_K3440019 | Osc1 | Pconst-RBS-LuxR-DT-Plux-RBS-MtrB-DT | Show that MtrB can be expressed under Plux in the presence of AHL. |

| BBa_K3440020 | Osc2 | Pconst-RBS-RhlR-DT-Prhl-RBS-RhlI-RBS-AiiA-RBS-GFP-DT | GFP reporter of oscillation in E.coli |

| BBa_K3440021 | Osc3 | Plux-RBS-MtrB-DT-Pconst-RBS-RhlR-DT-Prhl-RBS-RhlI-RBS-AiiA-RBS-LuxR-DT | Electricity production under oscillatory circuit in Shewanella. |

Because many of these constructs were long and would each require many days of assembling biobricks, we decided to order most of them from IDT Technologies as gene blocks with convenient restriction sites in optimal positions and tags to allow characterisation. We used those gene blocks as a starting point for our experiments.

The full circuit we designed for detection of PCB (it is similar for PFOS) is the following (Figure 3): the first construct produces bphR2 constitutively. bphR2 can form a complex with the PCB pollutant, which can activate the bphR1 promoter. LuxI is placed under this promoter and produces a QS molecule. The fourth construct produces RhlR constitutively, and RhlR can bind to C4-HSL to induce Prhl promoter in the third construct, which induces expression of LuxR, RhlI and AiiA. RhlI produces C4-HSL, which creates a positive feedback loop. On the contrary, AiiA degrades C4-HSL, creating the oscillations. LuxR binds to the 3OC6-HSL produced upon detection of PCB by the first construct. The complex can activate Plux promoter, which controls the expression of MtrB, the gene responsible for electricity production in Shewanella.

Figure 3: PCB detection circuit

MFC

The MFC set-up was designed thanks to literature and discussions with Amirreza Khataee from the Applied Electrochemistry department at KTH. We decided to go for a liquid-air hybrid set-up, with one reservoir filled with media and another filled with air. Circulation between the MFC and the reservoirs is created by a pump at 0.1 RPM. The chosen electrodes were each made of 2 squares of graphite papers stacked together. The cation exchange membrane used was a NafionTM. The disassembled microbial fuel cell is shown in Figure 6. The circuit was assembled as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Disassembled microbial fuel cell components

Model

The circuits were designed with the aim of creating a unique oscillatory electrical output when a certain pollutant is detected by E. coli. To prove that the constructs could give an oscillatory circuit, mathematical simulations were performed. An initial design inspired from literature was tested in silico and found to be unable to give unsynchronised oscillations for different pollutants. Therefore, the circuit had to be changed and improved for our purpose. The obtained models confirmed that the design was theoretically capable of giving oscillations when pollutants are present.

Build and experiment

Parts

For each G-block, we performed (with regards to each particular construct's requirements) the following series of experiments and characterisations (Figure 5). We first resuspended the G-blocks, PCR amplified them, and then proceeded to insert them in the pSB1C3 plasmid via restriction digestion with EcoRI and PstI enzymes. We ran gels to check the sizes of restriction digested parts, then ligated overnight with pSB1C3. All of this was possible because the G-blocks were designed with predetermined, specific restriction sites. We then transformed E. coli TOP 10 cells with the plasmids. We picked colonies on plates, ran PCR amplification and gels to check if the sizes were as expected and sent the potentially correct ones for sequencing at Microsynth AG. The selected colonies were used to make glycerol stocks and plasmid preparations. OD600 measurements were made for all, and then characterization experiments were performed. For parts containing GFP or mCherry genes, fluorescence measurements were made with a plate reader. For those with a Myc-tag, Western blots were made. We used Chromobacterium violaceum as a marker of AHL production (colonies turning violet when AHLs are detected). Finally, expression was compared between situations with and without pollutants (after viability tests in the presence of pollutants).

Figure 5: G-Block processing workflow

MFC

We determined from literature on Shewanella oneidensis' metabolism that S. oneidensis could grow, using lactate as a carbon source to optimise electricity production Pinchuk, 2010. As a result, we chose lactate as an additive to our minimal M9 medium. We decided to check that Shewanella oneidensis MR1 could be used in our MFC set-up to give an electrical output thanks to its MtrB gene. In order to do so, we had to prove that a biofilm could grow on the anode and that this biofilm did not grow when the MtrB gene was knocked out. Thus, we acquired two strains of S. oneidensis MR1; a wild type from Ute Römling's lab at Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden, and a MtrB knockout strain from Johannes Gescher, Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, Germany. We decided to monitor S. oneidensis biofilm growth by measuring the open cell voltage of the circuit with an imposed resistance of 1000 ohm. Thanks to Ohm's law U=RI, the current could then be determined.

Our first experiment consisted in putting the wild type strain on the electrodes, then assembling the MFC with LB broth in a reservoir, and finally assembling the final circuit (Figure 6) and measuring the voltage continuously. After a few days, we changed the media for fresh LB and continued to monitor the voltage. We then changed the media for minimal M9 media with lactate as a carbon source and tried to check that the biofilm growth was enhanced after a period of adaptation to the new media. Our second experiment was a control to check the necessity of having the MtrB gene for electricity production. We assembled the circuit with the MtrB knockout on the electrodes this time and measured current with LB as media.

Figure 6: MFC setup, where 1/green is the pump; 2/yellow is the air bottle; 3/purple is the media bottle; 4/red is the resistor; and 5/blue is the MFC

Analyse the results

Most of our constructs were successfully designed and transformed into E. coli TOP 10 cells. The sequencing results confirmed what our gels predicted for fifteen of our colonies. The specific results for each experiment (viability, transformation, Western blots, fluorescence) are presented in Results. We decided to focus on the MFC engineering results here.

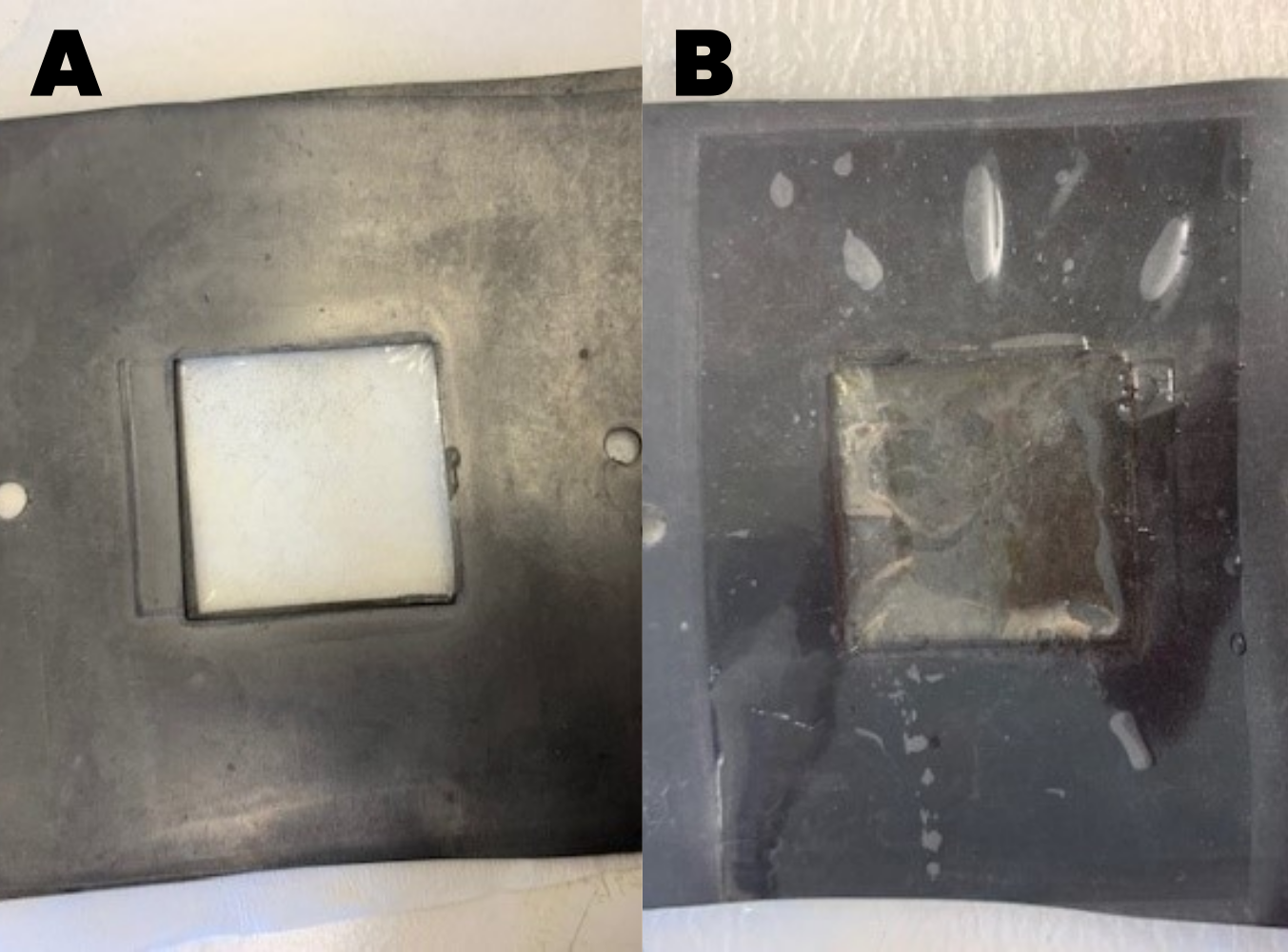

First, we observed with the open cell voltage over time curves that a biofilm could grow when S.oneidensis, wild-type was inoculated in the MFC and fed with an LB media (Figure 7). The voltage increased slowly and then underwent a high increase when the LB media was renewed. Seeing that the biofilm had grown, we changed the media to a minimal M9 media with regular lactate addition. As expected, the biofilm managed to adapt to this new media. At first, the voltage dropped and then it slowly grew back as it adapted. When we disassembled the MFC, we observed the biofilm directly on the membrane (Figure 9).

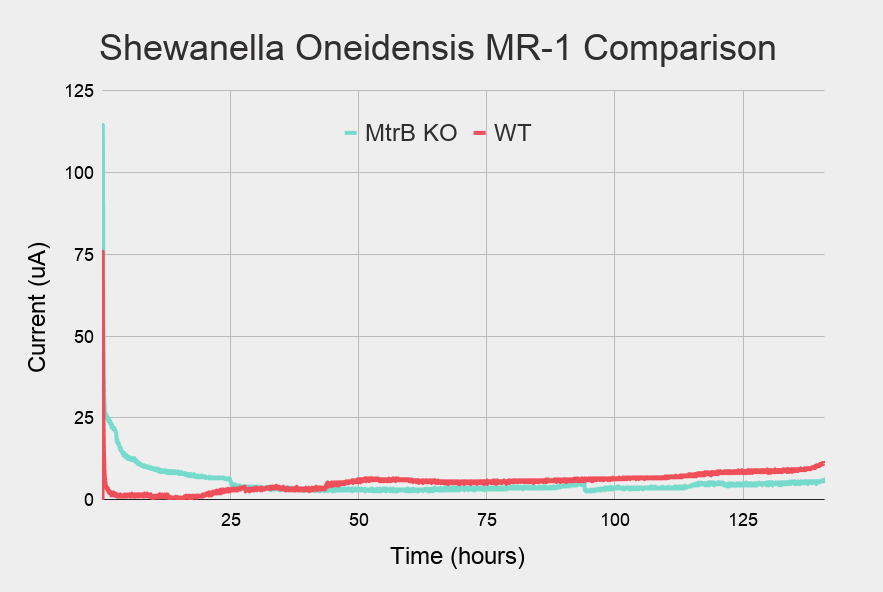

Those results were compared to the curves for the MtrB knockout strain (Figure 8). The Figure shows that the MtrB knockout could not produce a biofilm because it was unable to produce electricity, as predicted by literature. This result was confirmed when we disassembled the MFC and the membrane was free from any biofilm (Figure 9).

Figure 7: Current-time graph for Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 wildtype

Figure 8: Current-time graph for Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 MtrB knockout (cyan) and wildtype (red)

Figure 9: Membrane with A) no biofilm and B) biofilm

Discuss and conclude

An example of engineering success: our MFC success story

We managed to create and assemble a fully functional microbial fuel cell in which we have proved that a Shewanella oneidensis strain can form a biofilm on the anode when it is equipped with the MtrB gene. We have optimised electricity production by cultivating this biofilm with a minimal media to which we regularly added lactate to favour the electrical pathway. Finally, we have proved that this biofilm cannot grow without the gene. Thus, our biosensor cannot give a signal without pollutants, but will be able to give an electrical output when pollutants are detected and a construct expressing in an oscillatory manner the MtrB gene can be induced when pollutants are present thanks to the design of appropriate synthetic circuits.

Identify a problem to solve at i+1 = troubleshooting

During the summer, we had to optimise all types of experiments, from restriction digestions to Western blots. The key to troubleshooting is to find the origin of the problem. Most often, using positive and negative controls can both help you prove that your results are scientifically correct and help you find where problems occurred in an experiment. However, you might still encounter problems even with proper controls. We faced many problems with Western Blots, so we decided to share with you our very own troubleshooting checklist for Western Blots.

Quick troubleshooting list to help you when a protein does not appear on a Western blot:

Optimize your Western Blot protocol

- Make sure that you have appropriate positive and negative controls.

- Optimize your cell lysis.

- Think that your intensity might be too low if you have several products on the same blot, and one is overexpressed compared to the others. In that case you can either have separate gels or stop exposing the overexpressed product.

- If your protein might be expressed in another growth phase, adjust the timing.

- In our case, some proteins were expressed in the presence of AHLs and contaminants (under inducible promoters). If such is the case for you, try to increase the levels of inducers.

For cells that express GFP or mCherry or any colored/fluorescent protein, you might want to quickly check to the naked eye with a microscope under the right wavelength that expression occurs. Fluorescence measurements should also be performed and calibrated based on OD600.

Check your sequence. Sequencing your part is necessary, and you might as well do it before starting your Western Blots. The reason for this is that even if you have a band at the right size, it might still be another protein due to a substitution. Finally, if your western blot does not work, you can use sequencing to see if the problem is at the DNA level (a mutation to a stop codon could be an explanation).

Check your mRNA expression. If your DNA sequence is correct and you still don't have results on your blot, then you can try to see if the problem is at the RNA level by performing an RNA extraction.

Run a background check on your proteins to understand how they are expressed in their original host, and if possible find a paper in which it was expressed in your host. In particular, check the location of the product and the level of expression obtained in literature.

Check your cells. It might be that the protein product is toxic for the cell or that E. coli does not prefer its presence. The product might be easily degraded by protease. Thus, you might want to test growth with and without the construct and observe the number of colonies to see how your host reacts to the product. If that is the problem, then you need to change your host.

Coomassie staining can also help you to check your cells by counting total protein expression.

To increase expression of the protein, you can clone your plasmid on a low copy number plasmid or under an inducible promoter.